The Knight of Ships

A tiny clockwork timer chimes with the high, broken tone of a porcelain bell, and Selen removes her new arm from its shallow basin of water. Beneath its dripping, articulated ceramic plates, two roots of living green wood stretch out with a blind will. They find the scar where Selen’s flesh ends, two inches below her elbow on the left side. It doesn’t hurt when they constrict around the stump—some laboratorial sorcery of botanical drugs and interstellar dust—but Selen’s stomach still churns with sudden vertigo, and her nerves prickle as the roots find them and connect. Two more plates snap closed around them, hiding both roots and scars from view.

She touches each finger to its palm, bending the hinged knuckles one at a time in a stiff, jerking rhythm. The pressure feedback reaches her awareness a fraction of a second later. It will get better, the surgeon assured her; it just takes some time and some practice. She has spent a week in the infirmary on Oresia and two here at her mother’s estate on Varauso, and she hasn’t noticed a difference. She tries not to worry about it.

The floor is cold beneath her feet when she swings her legs out of the canopied bed and onto the polished stone floor, her toes meeting a wave pattern tiled in blue on a veined white background. It’s always cold on Varauso. Outside, behind a tinted screen that turns its livid colors to shadows, the planet’s eternal storms rage on at a temperature that would freeze a human being solid in seconds, even with the distant sun briefly at its zenith. Days are short here, with only eleven and a half standard hours between rapid sunrises, but Selen is still bound to the Sennekan military’s twenty-five hour clock. The estate’s engines hum even through its layered dampers, keeping its altitude level and its internal conditions livable, and crystals of ammonia and helium shatter into snow against the tinted window. Varauso’s winds howl like a congregation of distant mourners.

Selen pulls out her earplugs with her right hand and places them beside the dish of water. Almost instantly, her head aches from the noise, even muffled as it is, and the vibrations beneath her feet rattle her teeth. This is no planet for a pilot-knight. It’s no wonder her mother has been in a foul mood the entire time she’s been here—she must be constantly miserable. Selen, at least, will be leaving soon.

She pulls her sleeping shift over her head, again with her good arm, and leaves it on the bed. A draft of recycled air exhales from the overhead vent, yet another attack from the antagonistic house and its more hostile planet. Selen shivers and shuffles across the floor with all the speed her confused circadian rhythm can muster, holding her right arm across her chest for warmth and leaving the cold, artificial one hanging at her side. A wooden door set into the wall conceals her wardrobe, such as it is: it contains only her newly laundered dress uniform, a replacement flight suit of fine-grain leather lined with thick wool, its attachments dangling, and a formal gown that almost certainly won’t fit even if she could do up the fastenings one-handed. Fortunately for Selen, the royal delegate won’t expect the gown. Despite the arm, she’s still a few years from retirement and marriage, which means a few more years of uniforms. Things could certainly be worse.

Selen dresses, ceramic fingers clumsy on the buttons. She has laced up the boots so they can be tightened with a single firm tug, and she’s developed a bit of a trick to holding her belt with the artificial hand and fastening it with the fleshly one. Her dueling knife and baton, laid out on her bedside table, are holstered on her right and left sides, respectively. A pilot-knight isn’t fully clothed without them, and Selen is still a pilot-knight.

In the polished bronze mirror, a vulgar display of wealth this far from the Sennekan capital, Selen almost looks like herself. Leather gloves cover her mismatched hands, and her pressed sleeves, their distinctive phosphate blue a dull slate gray in the reflection, hide the rest. Pinned to her vest’s wide collar, heavy against her left breast, is a ceramic medal on a satin ribbon—the same ceramic as her arm, as well as both the ship she lost and its replacement, and everything else in the Kingdom of Senneka. It is glazed in white glass and stamped on its face with the symbol of a high, domed crown. If Selen had a choice, she would leave it off, or throw it into the seething atmosphere, but she doesn’t. On the back is the seal of King Avulash, and a notation that the medal was granted in the fifth year of his reign, may he live forever. The image preserves his face exactly as it was when he sat for his last portrait perhaps a year ago: handsome and young and blessed with a mane of glorious long hair and the distinctive aquiline nose of the Ramasuard line.

Despite the inscription, it was a sharp-faced courtier of no relation to the king who had pinned it to her chest. She had been barely conscious, badly burned, and missing an arm. She couldn’t even see King Avulash-may-he-live-forever, the man for whom she’d bled and frozen in the asteroid field outside the Gate, she was so far below his platform. Beside her stood the aging parents of those who hadn’t made it back, their eyes dry and their movements stiff and ponderous, as though grief had filled them up and hardened into stone.

The hum of the house’s engine grows louder and heavier as Selen descends the stairs. Churning orange-red light illuminates the estate’s first floor, setting abstract blue mosaics into motion like the sea she remembers from her childhood. There is no ocean on Varauso, only frigid, violent wind, and somewhere, miles below her feet, a metallic core almost as hot as a sun—or at least, that’s what the delvers theorize is down there. No one has ever seen it, and no one ever will.

Her mother sits at the breakfast table, the smeared remnants of quail eggs and a half-eaten pastry on the plate in front of her. She’s already dressed for the occasion in a high-collared gown that shimmers like silver water and clings to her slim shoulders. A pair of tapestries flank her, stretching from vaulted ceiling to waxed wood floor, each showing a tree worked in gold thread—the only vegetation in the estate, except for the roots inside Selen’s arm. Maryama’s rich dark hair has developed a shadow of gray in the years since Selen left for the academy, and her face is drawn, fine lines radiating from her scarlet-painted lips—an effect of the dry, recycled atmosphere inside the sealed estate as much as of age.

“Is it too much to ask,” she says, arching one thin brow, “that you do something with your hair? The royal delegation will be here any moment.”

Selen’s hand goes to her curls, and for a second she’s eleven years old again, stuffed into several starched, layered skirts for a court function. Though she’s her mother’s mirror, full red-brown lips and freckles over a wide nose, her hair is her father’s, and Selen is the only evidence that he and Maryama were ever in the same room together for longer than a minute. It doesn’t matter what she does with it; Maryama will find something to complain about.

“Good morning, Mother.” She removes her gloves with her teeth, prompting another twitch of her mother’s eyebrows, and sits down in the high-backed chair at the opposite end of the long table, letting her weapons knock against the slats. Its hard edges press into her thighs like the flat edge of a knife. Even the furniture hurts. Not for the first time, Selen suspects Avulash’s father gave Varauso and its estates to her parents as a punishment for some unknown transgression.

Maryama’s eyes fall on the pinned medal. “How are you feeling today?” she asks, a little softer.

Maternal comfort doesn’t come easily to Maryama. Selen appreciates the effort. “Fine,” she says. “Same as yesterday.” And the day before, and the day before that, ever since she woke up in the Oresian infirmary. Her exposure burns are healing, and her left arm hurts and doesn’t quite follow her commands. Maryama has heard it all already.

“It’s been nice, having you home,” her mother says, as though someone is pulling the sentiment from her mouth like rotten teeth. It’s sincere—pilot-knights do not wear masks of politeness and misdirection like courtiers do, and Selen can tell when her mother is lying, even through the distraction of Varauso’s incessant noise. This is the closest Maryama will ever get to saying she loves her only daughter before the delegate arrives and takes her away on her new commission.

Selen manages a smile, and says “Thank you,” but this isn’t home. Home was the castle on Hanoria, on a cliff overlooking the endless ocean under a warm yellow star. She had left it for the academy almost ten years ago. Shortly after, the king had given her parents Varauso, and Selen has never gone back to the planet and the house where she grew up.

A young woman she doesn’t recognize sets a plate in front of her. Five tiny eggs stare translucently at her like golden eyes. The pastry accompanying them is dry, and the red color of its jam filling is artificial.

But it’s sweet, and the eggs are salty and fried in oil pressed from some kind of seed growing in a floating hydroponic farm. It’s better than ship food. Selen eats it all. She would have even if it was ship food—habit from the field—but she’ll still miss this approximation of real cooking when she goes back out.

The house shudders as something equally large meets it in the atmosphere. Its stabilizers shake and whine, their dynamos spinning faster to take on the extra mass and awkward shape. The sound evens out to a deep mechanical hum.

Maryama grimaces, and Selen finds she’s mirroring her, grinding her teeth against the vibration and noise. The original owners of this estate hadn’t been pilot-knights, evidently, but they couldn’t possibly have just tuned out the constant fluctuations of the two massive engines under their feet.

“Your father’s here,” Maryama says. Selen doesn’t think she’s ever said Paleron’s name in their thirty years of miserable marriage. “The royal delegate is with him.”

Not only is the delegation on-planet, they’re at Selen’s doorstep already. She stands up, straightens her uniform, and picks an errant fragment of pastry from her teeth with her right thumbnail before putting her gloves back on. Maryama scowls in disapproval, but says nothing.

The entry hall spans the height and length of the house, with dark wooden columns that turn to ribs and a spine as they reach the vaulted ceiling. Selen’s boots tap against the polished marble floor, filling the space with echoes; Maryama’s shoes are soft-soled, and she follows in silence.

Perhaps for the first time in years, the platforms of Maryama and Paleron’s houses have joined together. Varauso’s winds shake the covered bridge between them, and electromagnets fire up and engage with a series of muffled thumps. Selen’s ears pop as the door seal releases. First the ceramic outer plates, and then the carved wooden inner doors, open to admit the royal delegation.

Selen takes her place by the door, standing at attention with her mother beside her. The house’s staff, all planetary natives with pale skin to absorb the far-distant sun and short stature from the weight of Varauso’s core, line up behind them, dressed in black tunics and trousers pressed to military precision and gleaming black boots, sharp and exactly identical. It seems they’d had a little more warning than Selen did of the delegation’s imminent arrival.

All of them are strangers. Her mother’s face is the only familiar one in the estate.

In a rush of compressed air and the sound of icy wind, the royal delegate enters Maryama’s house. He’s dressed in layers and layers of silk, sapphire blue and topaz yellow, belted around the waist with a scarlet sash embroidered with silver thread and tiny pearls—Hanorian pearls, most likely. The man himself is the picture of Oresian nobility, tall and long-limbed, with flawless bronze skin and black hair that shines like volcanic glass, falling to his waist in a series of braids bound in more silver. His robes brush against the floor with a sound like oncoming waves.

Behind him walks Selen’s father, dressed in a jacket of gold brocade she hasn’t seen before and a more familiar pair of high, polished boots. He gives Selen a half-smile and nods a stiff, cold greeting in her mother’s direction. The skin beneath his eyes is almost purple, as though he hasn’t slept, and he’s shaved his head, something that unsettles Selen even though she knows he’d be balding by now. His scalp shines in the gaseous golden light. His tightly-curled beard is gathered into a single thick braid, falling from the center of his chin and ending between the two parallel lines of lacquered wood buttons on his chest.

A dozen tall courtiers, each more beautiful than the last, file in after, a sea of shimmering blue fabric. Their exquisite, chiseled faces are as grim and still as if they were carved onto a door. With a sound of sucking vacuum, the door seals shut behind them.

The delegate opens his hands, spreading his voluminous sleeves to show their brocaded lining. He takes a breath.

When he speaks, his rich, resonant baritone fills the room, ringing from each wall. It’s as painful as it is beautiful. Selen clenches her teeth and tightens both hands into fists, the left a beat behind the right, to resist putting her hands over her ears.

“King Avulash Chanata of the line of Ramasuard is dead,” the delegate intones, somewhere between a chant and a song. “Long live King Avaren Sunyan of the line of Ramasuard.”

The house falls silent. Even the hum of the stabilizers seems diminished.

This has to be some kind of joke. Selen glances between her mother and father. The former is gray-faced in shock, while the latter stares at nothing, a muscle on his jawline twitching as he grinds his teeth.

She saw the king—at least, his distant outline against his high throne—fifteen standard days ago. He was twenty-nine and a half years old, barely older than Selen. Preparations were already under way on Oresia for his thirtieth birthday. Her right hand goes to her medal, and the ceramic imprint of the king’s face, as though she expected it to have disappeared with his death. The ridge of his nose scrapes against the seam at the end of her thumb.

“What happened?” Maryama’s voice is barely above a whisper, but it’s as loud as an engine in the stillness of the hall.

The delegate lowers his eyes, long lashes meeting high cheekbones. He’s well-bred indeed, but far too tall to pilot a ceramic fighter. Paleron, standing beside him, only comes up to his shoulder.

“As the living descendants of the line of Ysronak,” he intones, “your presence is requested at the coronation of King Avaren. It will be held in eight days’ time, by the reckoning of Oresia and its star.” He reaches into one voluminous sleeve and produces a sheet of heavy parchment, folded over into thirds and sealed with red wax.

Maryama frowns. She takes a hesitant step forward and accepts the parchment as though it’s a rogue fragmentation bomb, about to explode. Holding it between her thumb and a blunt forefinger, she retreats to her place beside Selen, leaving the wax image of a plumed desert bird untouched.

Selen was expecting a sealed letter. It was supposed to have been her new commission: the name of a haughty Oresian noble who had never been more than one star away from the capital, and of the division of fighters they owned and could send out to the far reaches of the galaxy. It would have a second seal, of said haughty noble’s family, smaller than the royal seal but demanding attention of its own.

This is not that letter. Someone owns Selen’s new commission—that was decided while she was still in the hospital—but she’ll have to wait to find out who it is. It doesn’t matter much, really. Under normal circumstances, she’d never meet the person who officially commanded her. All the letter would do is tell her where to report first and get acquainted with the pilot who was actually in charge.

Selen’s mother tucks the parchment into one of her own sleeves. She takes a breath, closing her silver-shadowed eyes, and her lips move in a brief, silent litany.

Fear, like a change in gravity, flips Selen’s stomach. It doesn’t matter whose ass is on the Oresian throne, any more than it matters who’s holding Selen’s commission. Selen will still be concerned with her ship, and Maryama and Paleron will maintain their strained truce and share custody of Varauso. Nothing important will change, right?

Maryama’s reaction says otherwise. Her eyes flutter open, and her face settles into a passable imitation of the courtiers’ expressionless masks. Only a single crease between her brows gives her away. “Thank you, esteemed delegate, for bringing us this grave news. Will you take some refreshment?” She holds out an arm, gesturing toward the opposite wing of the house.

The delegate turns like a dancer on the sole of one expensive leather shoe, and his entourage falls into line behind him. They move across the marble floor in perfect synchronization. Paleron follows, without so much as acknowledging Selen and her mother.

Maryama’s mask falls. She scowls at her husband’s retreating back, but her face soon gives way to a gnawing worry that Selen knows all too well. “Prepare some tea for our guests,” she says to the black-clad staff, and they disperse into the wing behind her.

“What’s going on?” Selen demands, whispering through her teeth.

Her mother shakes her head once in a sharp dismissal. “Not now, Selenar.”

Selen is about to protest that she’s a grown woman, that she’s been flying for a decade and seen combat more than once, that she almost died, but the argument sounds like a child’s even in her own thoughts. She flexes her ceramic fingers and scratches the place where the artificial arm clamps onto her skin. It only itches occasionally now. That’s something.

The delegation has settled into upholstered chairs in what might have been called a sunroom on a planet that received any sunlight. As it is, the huge glass windows show only a mass of yellowish cloud, swirling in on itself as it races by at a speed that would rip flesh from bone, and the perpetual shower of frozen crystals trapped within it. The distant star lends it a pale, watery illumination. The room is colder than the hall, the house’s warmth leaching slowly into the frigid atmosphere through the glass.

The courtiers sit in pairs, facing one another, gathering their silk layers around them. Oresia is a much warmer planet. These people are too refined to look uncomfortable, but they are. The woman nearest the door when Selen walks in behind her mother smiles and inclines her head in greeting before signaling to her partner, resting two fingers against her jawline. The man across from her folds his hands on his lap, glancing down and to the right.

They’re speaking a language Selen doesn’t understand, though she knows a similar dialect. Her signs are simple, expansive, able to be seen from across a stretch of empty space and through the windows of ships, and convey things like follow me or behind you or my hull has been breached.

“You must be Selenar,” the man says. “Your father says you saw action in the Theros system.” His face is sharply angular, with a nose like the one the late king has in his portrait—a distant cousin, perhaps.

“Selen,” she says, and then she remembers to smile. It’s less a correction than a peace offering, an attempt at connection to this person who is so alien to her that he might as well be from across the galaxy, rather than the capital a few planets away. Still, her hands meet behind her back, and she tugs her glove up over the inch or so of exposed ceramic plating. She’d had enough stares on Oresia, and more questions than she could answer.

The man smiles, showing perfect white teeth. “Selen,” he repeats. “You honor us with your service. As the representative of the Second Gate station, I think I can speak for the court.”

Selen’s eyes go wide. This is Shaeth of the line of Harilda, lord not of a planet but of a station surrounded by miles of metallic asteroids, bathed in the eerie gray light of the Gate instead of a star. His name and seal adorned the missive that summoned Selen to the field. Until this moment, she has never seen his face.

She wants to hate him. He is every inch the courtier, too tall for a ceramic fighter and too broad to have grown up on the station he rules, breathing recycled air along with every stray infection, his bones growing weak in the weak gravity. His opulent clothes were purchased with the wealth of the asteroid mines, not to mention the heavy tolls paid by any ship entering the Gate. When the pirates came, he was safe behind multiple layers of metal and ceramic, with a fleet of slow ships and their magnetic lances already at his command. Just in case, he decided to petition for a dozen fighters anyway, and he received them because the right amount of money found its way into the right hands. If there is a singular person to blame for Selen’s missing arm, and the deaths of five of her squadron—other than the king, to whom every pilot-knight ultimately answers—Shaeth of Harilda is that person.

She finds she can’t bring herself to care. Maybe she’ll be angry with him later, and lull herself to sleep with fantasies of throwing him out of his station to die of exposure like her friends did, but for now, he’s just another pretty face in a crowd of pretty faces.

“Thank you,” she says, and gives the lord of the station a stiff-backed bow. He smiles and turns back to the woman, continuing their conversation with a tilt of his head.

Selen’s mother is a dark silhouette against the window, staring out into the storm. Her father stands behind the delegate’s chosen chair, half the room away, his arms crossed over the polished buttons of his jacket and a familiar worried frown deepening the lines between his brows.

Selen leaves the sunroom. They can scold her for it later.

An attendant rushes by, carrying a tray of fluted glasses filled to the brim with bitter, amber tea. She notices Selen and stops, her movements so precise that the liquid doesn’t even shake, and holds out one glass.

“I’ll take two, if you don’t mind,” Selen says. She wishes she were being offered something stronger, both for herself and the other intended recipient, but this will have to do.

The attendant hands her the first glass, and she passes it from her good hand to the artificial one, thankful for the glove that keeps it from slipping through her smooth, rigid fingers. She’s not as graceful in heavy gravity as the attendant, and tea splashes onto the thumbs and forefingers of both gloves. Her right hand feels cold; her left only tingles in response to the moisture. She hopes the caffeine doesn’t make the Issanian wood behave any more strangely than it already does.

Both hands remain steady enough as the attendant continues on her way and Selen heads for the doors. Attached somewhere to her father’s estate is the ship the delegation came here in, which means that they have a pilot. Since no one in a uniform came across the sealed bridge, that pilot is hiding out somewhere away from the courtiers.

A sensor detects Selen’s footsteps, and the first set of doors shudders open, their wooden hinges groaning under the weight and the ceramic ones quiet. The release of trapped air stirs Selen’s hair, carrying with it the faint smell of sulfur.

Selen steps over the threshold and onto the plated floor of the bridge. The only sound dampening here comes from the narrow bands of silicone sealant between plates, and the wind is deafening, screaming all around her. At her back, the doors creak shut, leaving her in darkness, and a motor vibrates the bridge as it equalizes the air pressure again. An identical ceramic shell and an interior pair of grand wooden doors opens before her. Of all the reasons her parents can’t stand each other, a difference in decorative taste isn’t one of them.

Even the floor plan is identical. She turns right past a tall, graceful pillar and enters the dining room, where a young man in a familiar blue uniform slouches alone over a table meant to seat two dozen. A yellowing paper book lies open in front of him, the spine cracked up the center.

He looks up as she approaches and the doors close up again. “Selen,” he says. “I thought you might be dead.”

“Not yet,” she says. She puts one glass of tea in front of Halowey and hooks her ankle around a leg of the chair beside him to pull it out. “I see you’re flying royal delegates around now. Good for you.”

He grimaces at the glass, as though he thinks it might be poison. “It’s all right. I don’t like slow ships, but the nobles don’t talk to me much.”

“That’s something.” Selen slumps into the chair and takes a sip of her tea. It tastes of smoke and leaves that don’t grow on Varauso, even in the hydroponic farms.

Halowey folds down a corner of one page and closes his book. The cover shows a noble’s chiseled face on a body wearing a pilot-knight’s uniform, rendered in lurid colors.

“So,” he says, his tone flat, “what happened to you””

Selen leans back in her chair, feeling the hard wooden slats press against her back. One of her burns is itching all down her spine. She reminds herself that it only means it’s healing. “Pirates, out by the Second Gate. A magnetic lance hit my engine. Then I hit one of the bigger asteroids. Missed the mining rig by a couple hundred feet.”

“Huh. I bet Lord Shaeth was happy to hear that.” Halowey picks up his glass, examines it through a squint, and sets it down again. “You look all right, at least.”

Selen laughs, a sharp bark that hurts her chest. “I did lose an arm. Or half of one.”

“Bad luck,” says Halowey. “Sorry.”

She pulls off her left glove and waves ceramic fingers at him. “They gave me a new one. It’s got Issanian wood in it. I have to water it every night.”

Halowey looks up. “You’re serious?” He takes her plated hand in both of his and bends the wrist back and forth, peering at the green roots at the joint.

“It’s a new thing, I guess. I get to test it out,” Selen says. She can feel the pressure of his thumbs on her palm, and can sense the manipulation of her fingers a half-second after he moves them, but his hands might as well be ceramic themselves. Neither warmth nor softness transfers to her damaged nerves.

“I’ve heard of ships that have both. Ceramic plates over an Issanian ship, that kind of thing, out around the far gates.” Halowey releases her hand. “Does it work?”

“More or less.”

“That’s not so bad, then. You can still fly, right?” At Selen’s nod, he continues, “I knew someone who got a nasty bump to the head in a crash. Kept all ten fingers, ten toes, but couldn’t tell which way was up, even in heavy gravity. Never flew again.”

Selen thinks about being stuck on Varauso, staggering dizzily between her mother’s and father’s estates, for the rest of her life. Her marriage prospects, even after the years of negotiations that have already taken place, would dry up, so here she would stay. She’d rather fling herself into the atmosphere and let the coriolis storms grind her into a fine paste. It would be quick, and the freezing temperature would mean she wouldn’t feel a thing—not like a flaming wreck, or slow depressurization, like the pilots who didn’t make it out of the asteroid field.

She holds up her glass. “To the fallen?”

Halowey groans and gives his tea a baleful look. “Don’t make me drink this stuff, Selen.”

“Just one sip. It’s good for you,” she says. “And it probably cost as much as a ship. Don’t waste it.”

“Fine.” With a sigh, he raises his glass and taps it against hers. “May they rise again.” He takes a drink and pulls a face, poking his tongue out between his teeth and wrinkling his nose. It makes him look like a fussy baby and a wrinkled old man at once.

Selen laughs for the first time in weeks. She drains her glass and takes his. Halowey doesn’t protest.

He thumbs the corner of his book, ruffling the battered pages. “So I guess you’ve heard by now.”

“Yeah.” Selen can feel her face fall, and her heart sinks with it, pulled down toward the planet’s core. “I guess I have.”

It doesn’t matter, she tells herself again. Worrying about things above my station is only going to make my life harder than it already is.

“They crashed, you know,” Halowey says to the tabletop. “The king and his pilot. Got caught by a moon outside the Sixth Gate.”

That can’t be right. The tea turns sour in Selen’s mouth, and she holds her breath for several seconds before realizing she’s doing it. She reminds herself to swallow. “Yerula’s moon? The iron rock?”

Halowey nods. “That’s the one. No atmosphere. They’re saying they died on impact, but even if they didn’t…”

He leaves the rest unsaid. In either case, the king and his pilot had plummeted for miles through a black sky, the rust-red surface looming ever closer, just waiting for the end. At least Selen’s fall had been shorter. She’d barely had time to grit her teeth and close her eyes before impact.

“How?” she asks. “We all know about that moon. It’s impossible to miss.”

“I don’t know. I wasn’t there.” He scowls, stretching the smooth, tight scar. “I’m just telling you what my passengers were talking about when they thought I wasn’t listening.”

“Then it’s just courtiers’ gossip,” says Selen. “You know how much they like to talk.” They like it so much that there were probably seven other rumors Halowey didn’t even know about, because his passengers spoke of them in gestures and notes and the colors of their jewelry. And since most of them haven’t even flown through a gate before, and not a one has piloted a ship, they don’t know how completely stupid the idea is that the king’s own pilot would hit a huge, dense rock as it traveled its slow and predictable orbit.

Halowey’s shoulders rise and fall as he takes a deep breath. “You’re probably right.”

“You know I am.” Selen fits her artificial fingers into her glove and tugs it back up the wrist. “Listen, we’re supposed to fly, not worry about this kind of thing. There are a lot of people a lot richer than we are who can deal with it.”

“No, you’re right, and I’m trying not to think about it.” He runs a hand through his hair, a nervous tic Selen recognizes from the academy. “It’s just, I met the king’s pilot once. Esten of Lassala. He was the very best of us, and he’s definitely dead. I found that out before I’d even heard about the king.”

“So, then, what happened to him?”

“I don’t know.” Halowey slumps down in his chair and lets his head drop to his chest. “Seems like nobody knows. He was going to retire next year and marry. I saw his intended on Oresia. She was really upset.”

Selen would be too, with such a good match, not that her line would ever get anywhere near the king’s entourage. Sure, a royal pilot is often called a medical miracle, still being able to fly without being able to see past his own nose, but he wouldn’t retire to a barren world where there isn’t even ground to stand on. Esten’s intended is likely a year or less away from retirement herself, and now she has to find another husband. Bad luck for her, but it happens. Pilots die. Not usually from hitting an easily avoidable moon, but they do.

The distant sun is sinking already, and amber light slants across the table at a low angle. It will set in another hour or so. Selen’s parents will be missing her, and since they have the misfortune of being in the same house, they will already be arguing over who’s responsible for their daughter’s rudeness—in sharp glances, rather than words, with all the nobles present, a cruder version of the court’s silent language.

“I should get back to it,” she says, getting to her feet. Maybe she can still prevent the worst of the storm that’s about to rage inside her mother’s house. “You take care of yourself, Halowey.”

He picks up his book again and finds the dog-eared page. “I’ll try my best. Maybe I’ll see you again.”

“I’d like that.” It probably won’t happen. She’ll be flying her own ship back to Oresia, and then she’ll be off on her new commission. Or at least she hopes. Still, it’s been weeks since she’s been able to speak with another pilot, and it’s felt like a hundred years. Maybe after she retires, she’ll be able to talk to her mother better. Is it a sudden change, once you’ve stopped flying, or does it take years to start to care about politics and appearances?

She takes the empty glass as well as the half-full one. Some of her mother’s glassware wandered into her father’s office once, back in the seaside castle on Hanoria, and Selen doesn’t need to experience the aftermath of that again. If she can say one thing in favor of Varauso, it’s that her parents can keep their own cups in their own houses.

The door to her father’s house closes behind her, and for a moment she’s in no-man’s-land, with the eternal storm shaking the walls around her. Thunder rolls far beneath her feet. Halowey is probably having a hell of a time on this planet. No wonder he was hiding out by himself.

The opposite door stares her down. It’s only for a little while, she tells herself. Just go smile and bow and act interested, and you’ll be off to Oresia and your new commission in no time. You have your own ship; you don’t even need to fly with any of them.

Or she could just leave now.

The thought fills her with cold dread, a child’s fear of the unknown consequences of disappointing her parents, but Selen isn’t a child. Even her mother can acknowledge that, now that she’s got a medal pinned to her chest. Selen bumps her ceramic thumb against the imprint of the late king’s face. There will be a funeral on Oresia, and his brother’s coronation, and she should be present for both, but there’s nothing saying she has to fly with the delegation or her parents.

They’ll both be furious. They might even stop fighting each other long enough to join forces against me.

And it is at this moment, as Varauso’s storms crash against the plated walls of the bridge, that Selen realizes she doesn’t care. She saw the pitted, barren surface of the asteroid fill her canopy and felt her ship crack like an eggshell under her. She heard the hiss of slow depressurization and felt the dead cold of the vacuum creep in. By the time she lost consciousness, she had already noticed that she couldn’t feel her left hand. Waking up again came as a surprise. There is nothing in the reach of all twelve gates that her parents can even conceive of doing to her that could even compare.

There never was.

So, they’ll go to Oresia and then return here, alone in their separate houses floating in the furious sulfuric winds, and be angry with her. The delegate and his courtiers will talk, but that’s what courtiers do. Selen won’t have to hear any of it.

She steps into range of the sensor, and the door opens with another complaint of wooden hinges. The beautiful, empty hall, the perfect mirror of the one she just left, stretches out in front of her. As she hurries across and mounts the stairs, afraid that if she stops moving she’ll lose her resolve, the only sound is the patter of her boots. The house’s dampeners keep the guests’ very important and utterly incomprehensible conversation confined to the sunroom. If she can’t hear them, they can’t hear her, and no one will ask her where she’s going. She shuts the door to her bedroom behind her anyway, just in case.

She’s still carrying the glasses. She finishes the last of the tea—the caffeine will help her stay awake after three weeks of sleeping more than twelve hours at a time—and leaves the cups on her bedside table, beside the basin of water. She picks up the timer, but leaves the dish. It looks too valuable to risk it knocking around in zero gravity. Her arm will have to readjust to drinking out of a canteen. If Selen can do it, it can too.

Every creak of the house, every change in the hum of the stabilizers, could be footsteps on the stairs. Selen’s pulse quickens, as though she’s hiding a stolen pastry or a raunchy novel, the sort that her mother forbade but she read more than her fill of once she got to the academy. She starts inventing a story, one to have ready when the door inevitably opens: my arm needs water, it hurts and I need to lie down, I wanted to get changed into something more formal.

She unhooks her belt with her good hand and tosses it onto the bed, weapons still holstered. The blankets muffle the clatter. She bends down and crawls underneath, laying her new arm on the floor and reaching with her good one to find her pack in the darkness and drag it out into the light. It still has some weight—dehydrated rations and water sealed into ceramic bottles with wax.

It takes seven days to fly to Oresia. The bag was packed for her there, when the surgeons thought she could make the flight to Varauso herself, but her left hand was so clumsy that she couldn’t operate the controls. A slow ship like the one Halowey flies brought her here, towing her replacement fighter.

What if I can’t fly?

The pair of unbroken glasses on the nightstand prove that she’s more dexterous than she was, but the fear remains. She pushes it aside. She was born and bred to be a pilot. The Oresian court wouldn’t have given her another ship if they thought she was incapable.

The Oresian court also let Lord Shaeth have twelve fighters he didn’t need, but she’s going to choose to trust them, because the alternative is flying to Oresia on Halowey’s ship with both of her parents and all the gossiping courtiers.

Selen’s dress uniform goes into the pack, along with all the undergarments she owns, all of them plain and comfortable and an off-white that’s nowhere close to her skin tone, and she puts on the flight suit.

After struggling with the first five shiny, brand-new wooden buttons that go up the front, she figures out a trick of holding the placket flat with her left hand and shoving the button through with her right. She flexes her ceramic fingers again. They’re still just a little too slow, and she can’t feel anything with them. If she is facing a lifetime of learning new one-handed ways to get around, she would have rather they just told her so.

She curls the hand into a fist, opens it, and clamps it around her other wrist. Her grip is getting stronger. If nothing else, she’ll be able to make the trip from here to Oresia. It’s not like she has to go through a Gate yet. She ties the lacing at her collar, not as tightly as she would like, and tucks the ends of her sleeves into her gloves. Within seconds, the chill of the house is forgotten. The new leather creaks as she lifts her arms to pull back her hair.

That done, she takes one last look around the room. It isn’t hers, not really, though no one else will sleep here until the next time she’s on this planet. Is there another room, just like this one, in her father’s house?

Hard-soled shoes tap a quick, even rhythm on the hallway floor. Selen’s breath catches, and her eyes go to the door. She considers kicking her pack back under the bed, but she’s already wearing her flight suit. None of her prepared excuses will work anymore.

The footsteps pause for one beat in front of her closed door, then another. Selen stands still, hardly daring to breathe, as though that will help. She’s being foolish. Her parents can’t stop her from leaving, and neither can the delegate. All they can do is disapprove. She just doesn’t want to have to see it.

Ten years of flying and a near-deadly crash, and she’s still most afraid of her father and mother. Some war hero she is.

The person outside her door walks away, their steps fading into the white noise of the house. Selen lets out a breath. It doesn’t loosen the tension in her chest, like a fist around her sternum, its fingers laced through her ribcage. Suddenly, the house seems huge, as big as the planet, and she’s all alone while her parents glare at each other and pretend they’re happily married for the sake of the courtiers. She’s angry that the person in the hall was neither her mother, come to check on her ailing daughter, nor her father, to tell her she’s been a very brave girl and he’s so proud of her.

She laughs, but it sounds more like a sob, and it burns her throat and behind her eyes. This house has turned her into a child again, and she never was a child in this house. She’d never been in this room before two weeks ago. Her reflection in the bronze mirror, suited up in distorted gray-blue—and that mirror is yet another thing that wasn’t present in her childhood—looks at her reproachfully.

I need to get out of this house.

She’s had that thought before, back on Hanoria as well as earlier this week, but now she has the means to do it. She belts on her weapons, slings her pack over her shoulder, and walks with a confidence she doesn’t feel into the hallway.

The house’s fans are running, venting the kitchen exhaust out into the atmosphere. Apparently, it’s time to feed the delegation. Selen quickens her pace, half-jogging past her mother’s room and the pristine guest rooms with their stiff white linens, turned golden by the clouds’ evening color through the high windows. At the end of the hall is a hidden door, covered in the same wood paneling as the walls, that leads to the back stairs. Selen places her hand flat against it and pushes it inward. The latch clicks, and the door swings out.

Selen can hear Varauso’s winds screaming, even through the house’s layers of shielding and insulation. Grimy, dim lamps hang from the ceiling of the staircase, casting shaky yellow light onto the dusty steps.

She rounds the bend in the staircase at a run, passing the kitchen door before it can open and someone can catch her. She’s so close—her ship is on the other side of the wall at her right, tethered to the house by means of a web of steel cables secured to her hull with ceramic clamps, and despite the grave breach of decorum she’s committing, she has every right to take it. She just can’t shake the feeling that she’s breaking every law that exists in this sector by embarrassing her parents while the delegation is here.

Two members of said delegation are in front of the back airlock, pressed up against the horizontal lever that stretches from one side of the door to the other.

Selen grabs the handrail, the soles of her boots skidding underneath her. She comes to a stop just before she slips over the edge of the step. Her mouth opens, but her mind goes blank. There’s no good reason for her to be here, bag packed and dressed for a flight. She was so preoccupied, she didn’t even notice them.

The woman on Selen’s left sees her and squeaks. In a rustle of sapphire silk, she stuffs her full brown breasts back into her bodice. Her partner tugs at her own clothes, pulling several layers of skirts down over her bare thighs. Both women’s eyes go wide like frightened animals’.

“Sorry,” Selen murmurs. She puts her hands up and looks down at her toes. It’s the polite thing, but she also doesn’t want to recognize either of these women, in case their tryst by the airlock leads to some kind of scandal, as these things often do. Courtiers’ marriages are just as fraught as pilots’, though they like to tell themselves otherwise.

There’s more rustling and shaking of silk as the pair puts themselves back together. Despite her opinions on the nobility, Selen can’t deny that they’re both gorgeous, even from a glance. She counts back to the last time she had a similar encounter, and stops when she realizes it’s been longer than a standard year; possibly even longer than Varauso’s year, but there’s no need to make herself feel worse. The name of the lovely young man involved, a fellow pilot with especially clever fingers, has escaped her, though she distinctly recalls the burnt-oil smell of the shipyard where she met him.

“You’re Paleron’s daughter, aren’t you?”

Selen looks up, trying not to let her encroaching panic show on her face. Her mouth stiffens and her teeth clench. Two perfect faces look back at her, both flushed with swollen, red lips; the woman on the left has a roundness to her high cheeks that’s no longer fashionable but only makes her more attractive. Her partner is taller and more familiar. She was talking to Lord Shaeth back in the sunroom. She’s younger than he is, though it’s hard to tell with nobles and their creams and potions that keep Oresia’s dry desert air away from their skin, but the fact that he deigned to speak with her—and in a secret language, no less—means she’s someone of importance. Someone whose love life has already been decided for her, whether that’s marrying into the fiefdom of the Second Gate or producing several identically beautiful children to rule a different, barely habitable planet.

“We never saw each other,” she says. Maybe she’s older than Selen thought, because she speaks with calm, measured authority. She’s used to being obeyed.

Selen isn’t going to argue. She puts on her most winsome smile, though she’s out of practice and it feels strange stretching out her face. “Not even once.”

The woman nods once in sharp acknowledgement. She takes her partner by the hand and pushes past Selen up the stairs. Selen puts her back against the wall to let them pass. The other woman mouths a silent thank you over her shoulder.

Selen pulls up the hood of her flight suit, pushing her hair inside until the elastic edge comes down to just above her brows, and she puts the goggles over her eyes. The breathing mask comes up underneath it, covering the last of her exposed skin. She grips the airlock’s lever in both hands and pushes it up. The soft silicone seal releases with a puff of cold air.

Selen steps through, pulling the door behind her. It’s heavy, and it closes with a solid thump. She hopes the house’s dampers absorb that sound better than they do the wind. Varauso wails as the relative warmth of the setting sun departs, and the temperature difference behind the approaching terminus spurs on the storm. An icy rain shatters upon the ceramic plates above her head with a sound like high, discordant wind chimes.

She takes a deep breath through her mask. The suit vibrates down her arms and up her back as a series of valves opens, drawing in the breathable air of the house. Outside the insulated walls, it’s cold enough to make her teeth ache, but the suit keeps her skin from freezing. Without an external tank, she’ll have two minutes of air, more than enough to free her ship and climb inside. It was one of the first things drilled into her at the academy. One more breath, and she opens the second airlock.

A semi-circle of inwardly curving plates shields the vehicle bay from the worst of the wind, but the cold hits her like a punch to the gut. Without her suit, she’d be just more ice in the atmosphere. She staggers onto the platform, dragging on the door with her weight until the lock reengages.

The graceful curve of her ship’s hull rises up before her, turned gold by the last light through Varauso’s yellowish cloud cover. She calls it the Sea-Bird, after the gulls that nested on the cliffs below the house on Hanoria. Its wings stretch out from a small, rounded hull, pointed at the nose like a bird’s beak. The hinged feet of the landing gear grasp the edge of the dock. At the back, under the tail, the huge turbine that will let her get off this planet lies dormant.

One by one, she unhooks the clamps that tether her ship to the platform, laying the cables down carefully so as not to create more noise. The wind comes into the shelter and sweeps under the ship’s wings, rocking it gently from side to side. It wants to fly.

Selen turns a wooden handle on the starboard hatch. Its spokes are already rough and pitted from the weather. Two full turns and the hatch pops open; another turn and the handle comes loose. She tucks it under her replacement arm and lifts the hatch over her head.

Her last ship was named Tinissen, after the heroine of a novel she’d read at the academy, and it was identical in every way. If not for the shiny new padding on the pilot’s seat and the utter lack of carbon dust on the controls, Selen could convince herself that this was the same ship. She tosses her pack and the detached handle behind the seat and slides in. The cushion is a little stiff, and the hinges creak in reluctance as she pulls the hatch closed.

“My name’s Selen,” she tells the sleeping instrument panel, the mask muffling her voice, “and you’re the Sea-Bird. Are you ready to fly?”

Selen wraps her left hand around the first lever and gives it a firm push. The engine spools up with a high-pitched whine, and the ship hums a deep, resonant note. She’s ready.

The lever to the right of the helm is stiff from disuse, and Selen has to put her gravity-enhanced weight behind it to disengage the landing gear. A hydraulic hiss flows around the cockpit, and the claws open.

Just a little more. Another set of hydraulics kicks on, starting the air recycling and the internal heat, and a bellows breathes a steady rhythm at the back of the ship. Selen opens the vents above her head, and warm air blows over her, fogging her lenses. She waits until the indicator above the helm turns over from red paint to a friendly blue before she takes her goggles and mask off. The humidity clears, and the smells of ash from an industrial kiln and the dry dust of the Oresian desert fill the cockpit. It smells like home.

Another lever on her left turns the turbine toward Varauso’s heavy core, and the Sea-Bird rises from the platform. Selen puts both hands on the helm, turning it gently to the left and right, feeling the wind catch her wings. The pressure feedback on her left hand could still be better, but she can fly. She turns away from the house, and her ship falls into a sea of roiling golden cloud.

The planet makes itself known at the back of her mind, a huge dark presence beneath her feet. At the edges of her awareness, Varauso’s nearer moons are smaller, brighter pockets of gravity. The largest of them, a block of ice big enough to be a planet on its own, is a few degrees shy of being directly above her. She lets the ship list away from the house until she finds a strong thermal that lifts her wings up into a pale bank of the storm. Ice crystals shatter against her glass canopy. The clouds swallow her mother’s estate, and Selen feels her stomach lurch, from inertia as well as guilt at not at least saying goodbye.

She’ll see her parents on Oresia, where she hopes both she and they will be far too busy with the king being dead and his brother being crowned for the furious questions they’ll have. She has seven days to come up with an excuse.

Her engine hisses and whines as it struggles against the planet’s mass. The platforms on which its inhabitants live hover at an altitude that makes the gravity almost comfortable, but Selen’s weight still pushes her into the stiff new cushions of her pilot’s seat. She eases the throttle forward and feels the dynamo vibrate under her feet as it spins faster and faster.

And then the planet lets go, releasing her into a black sky. The sulfurous clouds fall away behind her. Varauso’s sun is a brilliant yellow point in a tapestry of crystalline stars, and Oresia shines orange-red and steady beside it. Rising above Selen’s left is the first moon, a huge, pale blue crescent shadowed by the planet.

The noise of her engine quiets. She pulls the helm toward the arc of the moon and cuts the throttle, letting the uninhibited inertia of the void carry her away from Varauso; from its gravity and its noise and its obligations. For seven days, she’ll be free.

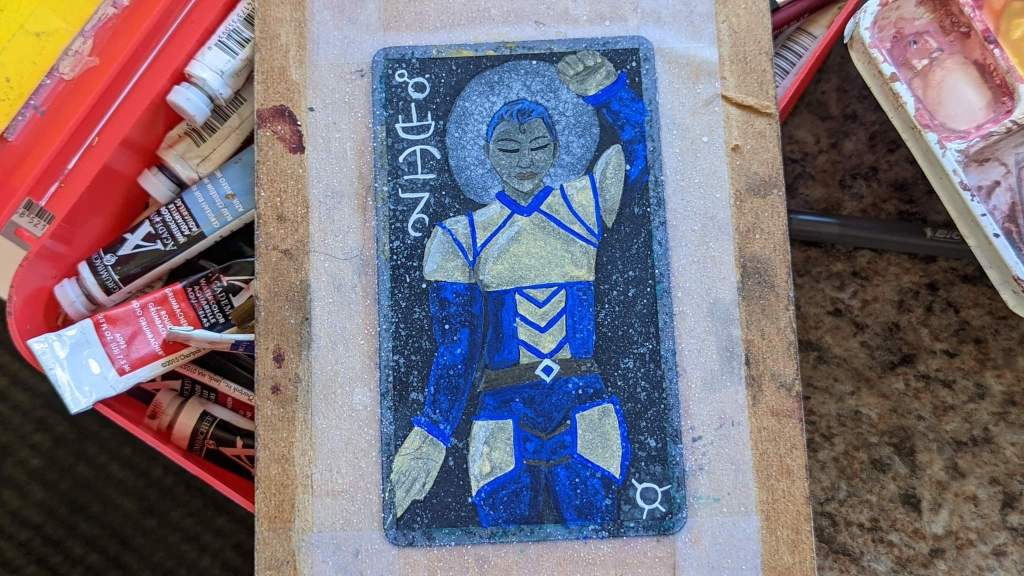

Thanks for reading! There will be more someday, and a Tarot deck painted by Brooke Marie Miller of the Figuratively Speaking Tarot, but for now this project will be on hold until I finish one of my others. As always, I appreciate you and welcome your feedback!

4 thoughts on “The Tarot of the Gates, Chapter One”