In which the tale begins.

Listen. Let me tell you a story.

I will tell you of my journey, from the ocean at the other edge of the world to the mountain of iron, beneath which slept a horror of an age long past.

I will tell you of the daughter of the stargazer, who found me on the northern wastes at the end of my long winter.

I will tell you of those who dared to defy the seven gods of the citadel.

And I will tell you of the barefoot prophet, for the man who now sits on the throne of Phyreios is not the same as the one who walked among its people in the days before the cataclysm.

It is fitting that here, where all journeys end, I should begin where my journey began. When I was a young man, I left my father’s hall in search of the great lind-worm of the far northern sea. I had told my companions a tale of the grand adventure and heroic deeds that would be ours on this hunt; in truth, I fled the wrath of my father and the duties that had fallen to me, his only son and the heir to the lands of the Bear Clan, as soon as I had come of age.

Fearghus saw through the lie I spun for myself and the others. We had shared a bed for three seasons, each of them far too brief, and he knew me best of any. Perhaps that is why he hesitated, while the other young warriors were eager. Still, I did long to prove we were mightier than the worm, and to return to my father’s hall as a company of heroes. It was foremost among the monsters that inhabited my people’s legends, and to meet it and live was alone worthy of many songs. I aimed to be the one to slay it, and be remembered forever.

It was this that persuaded Fearghus at last: our names would be joined in song for all the ages to come.

We left in high summer, when the sea ice had receded toward the top edge of the world, and the waterways flowed swift and free. In a mighty longship we followed the spouts of the whales north, to where the lind-worm hunted among the floating mountains of ice. The summer sun never sets in those far reaches, only touching down on the horizon each night to bathe the sea in fiery bronze light. On one such evening, when the ice shone gold as a dragon’s hoard, we caught sight of the worm.

Like a distant mountain peak it arched from the water, unfurling its coils and catching the sun on the shimmering sail on its back. The drum beat faster, and by our mighty oars our ship surged forward after the beast. Fearghus stood at the rudder, steering us true, the wind in his copper hair as we darted through the waves. I waited in the bow, a harpoon tipped in razor-sharp obsidian at the ready.

The sky darkened with black clouds, and a blast of wind tore across the sea and into our sail. Soon, it was as dark as the night we had not seen for nigh on a week, and an icy rain lashed down upon us. Our oars carried us into the storm, as waves rose up around us and the arc of the lind-worm’s sail stretched skyward. The monster loomed larger as we sailed nearer and nearer. I stood in the swaying bow, the harpoon to my shoulder, waiting for my chance.

The lind-worm dove, sending a wave into the side of our boat, drenching my companions and me in frigid water. I wiped the salt sting from my eyes and squinted against the thrashing rain.

The worm rose up again, a dark shadow against the roiling sky. I could have reached out and touched the black expanse of its side. A flash of lightning behind its massive head ignited its shining onyx eyes and its terrible fangs, jutting from the abyss of its mouth like magnificent curved blades. It drew back to strike, to bring its jaws down on the boat and sever it in two.

I braced my feet against the hull and stared the monster down, and I laughed with the mad joy of the hunt. With all the strength I could summon, I hurled the harpoon into the worm’s open mouth. It flew between its fangs and embedded itself deep into the soft flesh of its maw. An eerie, piercing screech cut through the din of the storm.

The lind-worm fell back into the waves. Whether it was dead or merely retreating for another attack, I do not know even now, for when its head hit the water a towering surge swept over the boat. Our mast snapped with a terrible crack, and the hull turned over. I was thrown from the bow. I remember the sight of Fearghus clinging to the rudder, the cold embrace of the violent northern sea, and after that, darkness.

I awoke on an unfamiliar shore, on gray sand under a softer gray sky. The storm had passed. A rocky beach stretched out on either side, a narrow band against the steely, endless ocean. Behind me stood a long range of mountains, all shrouded in fog. All that remained of my ship were a few broken timbers, washed up beside me. But for a pair of sea-birds circling far overhead, I was alone.

I shed the remnants of my ruined armor and walked along the sand, calling Fearghus’s name until my throat was raw. I burned the timbers as soon as they dried, in the hope that someone might see the fire when the sky dimmed in the evening.

No one did. For weeks I paced the beach, burning what I could find among the rocks and eating what I could catch with my hands. Two more of my companions came in on the tide during that time, their clothing rotted away and their flesh pale and bloated. Fearghus never appeared, neither as the man I had loved nor as his lifeless corpse. I stood in the gloom, in the gathering clouds of the false evening, the shapes of dead men and driftwood at the edges of my vision, and I swore to the gods of the sea and the mountains and of the beasts roaming among them that I would do whatever they asked, sacrifice anything they desired, if they would only return Fearghus to me.

They gave me no answer. It would be a long time before I would speak to any god and hear a reply.

Winter came swiftly in the north. The unbroken day came to an end, and the sun set for the first time. Each night that fell after was longer and colder than the last, the whales departed for warmer waters, and little by little, the sea-ways sealed shut with ice. Even if I had a boat, or wood to build one, I would sail nowhere until spring returned.

In the months that followed, I headed east, toward where the songs told of a passage southward through the mountains, away from the lands of my people. I could not have returned home even if I had wished to, but my choice was made. I would not go back in disgrace, without my companions and without Fearghus. I walked until the winds blew cold and the nights endured long enough that I was forced to seek shelter and build up what stores I could before the snows came.

I may have gone a little mad in the long dark. I would not have been the first to do so. Just as the sun never set in the summer, it did not rise in the depths of winter. When the moon was below the horizon, shimmering lights filled the black sky, emerald green and blue as the summer sea, shot through with bloody red. I saw shapes in that awesome and terrible blaze, ships and faces and the luminescent sail of the lind-worm, undulating between the stars, so vivid and so near I thought I could grasp them.

The snow stopped and the sun returned, as they must do in good time, though I have no memory of the passing of winter. My stores dwindled, and I left the cave in which I had sheltered, continuing on my way east until I came across the fabled passage south. The forbidding wall of stone opened up before me, and I knew that I had traveled farther than any of my people before me—and I had survived as an exile in the long winter, a feat few have accomplished.

I am called world-treader, and thus I earned the title: from the sea at the edge of the world I journeyed through the bare black mountains, where none had dared tread since the time of the oldest legends. My boots wore through, and I fashioned crude replacements from bark and hide; I ate what I could find in the underbrush—roots, and quick scurrying creatures, and berries when the spring, as slow to arrive as the winter was swift, at last bloomed in those lands and turned them all to green.

By that time, I had reached the foothills south of the peaks, and I could see the vast tundra stretch out ahead, flat and featureless as the gray sky hanging above. The mountains lay at my back, as did the whale-road that would return me to my father’s house. Other clans lived in the shelter of the low hills, where the soil was richer than the mountain passes where the Bear Clan hunted and fished instead of planting, though their villages were well out of sight. I could have tried to seek them out, to beg of them the hospitality held sacred across the harsher climes of the world, and return to my people when I recovered my strength—or I could have stayed, and lived out my days as one of their hunters. I chose instead to continue south and east, to the expanse of the tundra, so alien to my eyes long accustomed to a sky fenced in by mountains.

I came to a river that erupted from the rock and tumbled south, darting through the last of the hills and bending west before falling out of view. The first of the red-bellied salmon hurled themselves into the air in their rush to swim upstream, water droplets glistening behind them. Hungry as I was, and with only the most rudimentary tools at my disposal, I could not resist the lure of so much food so readily gained.

But it was not to be so easy. One of the mountain bears for which my clan had been named stood guard over this river, at a wide, shallow bend before the waterfall, standing watch and catching the leaping fish in his mouth. I approached with quiet footsteps, in the hope that if I appeared as no threat to him, he would let me fish and cross the river in peace. I was alone, after all, and without weapons.

The moment I set foot in the water, the bear rose to his full height, casting an elongated shadow across the river. On all fours, he had been close to as tall as I, and now he was nearly twice that. His great forelegs ended in wicked black claws, and his coarse black fur, thick as a gambeson, faded to brown on his belly. He roared, baring sharp, yellow teeth. The sky swirled with birds, startled from their perches on the gnarled trees.

I retreated into the sparse cover of the wood, keeping watch on the bear. He did not leave the river until nightfall, and by then it was too dark for me to cross with sure feet, and I could no longer see the fish. I slept in the crook of a tree and woke before dawn, but he had already taken his post when I returned to the river. With another roar, he turned to me, rearing back to swipe at the air with his claws.

Again I retreated to the trees, determined that I would defy him. The Bear Clan did not earn its name by having a lesser courage than a beast such as this. I found a sapling not yet twisted by harsh wind, and a large enough piece of flint to sharpen into a point. Lashing them together with a leather strip torn from my tattered clothing, I devised something like a spear. With this in hand, I went back to the river.

The bear bellowed his challenge as soon as I waded into the water. I bared my own teeth, as small as they were compared to his, and growled back, advancing until the river was knee-deep and he was within the reach of my spear. This only enraged the bear, and he drew up, his first blow swiping over my head. I struck with the spear, but it glanced off his fur, and I reeled back to avoid his next attack. He drove me all the way to the riverbank before I saw an opening. He stood, raising both paws to crush my head, and I drove the spear under his arm, cutting through fur and flesh. The force of his weight drove the point in, and the bear was dead by the time his bulk fell on me.

The river’s strong current helped push him from where his body pinned both my legs. I worked myself free and sent the birds wheeling again with a frenzied cry of victory. I ate well that night, and for some time after, on both the meat of the bear and on the fish I was now free to catch.

I crossed into the tundra as spring gave way to summer. The air swarmed with biting flies, and herds of great elk moved through the mists, their antlers scraping the heavy sky. At night, as I lay beneath almost-familiar stars, I heard the far-off howls of wolves pursuing the elk across the sodden green landscape. They stalked me as well, but I was not as tempting a meal as the new calves the herds protected.

Summer was brief, and my journey was long. The last of the fish and bear meat ran out, and there was little to eat in the rough grass. I grew weak as I walked, and the land turned from green to dull brown beneath my feet. If it were not for the northerner’s sturdy constitution, I might have starved, or taken ill from eating raw meat when there was nothing to burn.

I came then to the forested hills on the eastern coast. Winter was on that horizon, and with it the dread of the oncoming snow and the ice that would trap me once more. I was determined to continue on, to find more fertile lands before another long winter slew me at last. Lowland hunters stalked those hills, building up their stores in the late autumn, and I avoided them. They would have seen me as a threat to their villages, as I would have if they had come to mine, and I knew I was not strong enough to fend them off. If they were aware of my presence, they did not acknowledge me, and in another week I reached the shore. There, an icy wind sang of the nearness of the frost.

My strength faded, and I would not get much farther on foot. With a few sharp stones, a hatchet one of the hunters had lost in the woods, and a fire coaxed to life and sheltered from the wind, I hollowed out a boat from a fallen tree. It was crude and its balance was poor, and I soon found it had a slow leak, but it would float and bear my weight without capsizing. I gathered as much food as I could find without crossing the hunters’ path, and sharpened sticks to hunt on the sea if the gods would allow it, and I pushed off as the first snow fell over the water.

With the coast at my right, I sailed south. My people have few stories of the lands beyond that shore; travelers from the south never dared venture into the tundra, much less into the mountains beyond, and we never crossed into their lands. I knew not what I would find at the end of my voyage. Perhaps, having nearly reached the top edge of the world in pursuit of the lind-worm, I would end my tale by falling off the opposite side. The ocean might have continued without end, and I might have sailed forever, my rough boat continuing long after my body had died. How different this final harbor is than what I imagined then.

At long last, I landed in the bitter cold of midwinter, on a grassy plain covered in snow and encrusted with ice. I was frozen and half-starved, with little idea of who I was and none whatsoever of where I was going, but I was alive.

In the distance, a lone rider approached.

I hope you enjoyed this while I wait for publishing news! Thanks for your patience.

Just for fun, you can check out the earlier version of this chapter here–one of the very first posts on this blog! This story has come a long way since then!

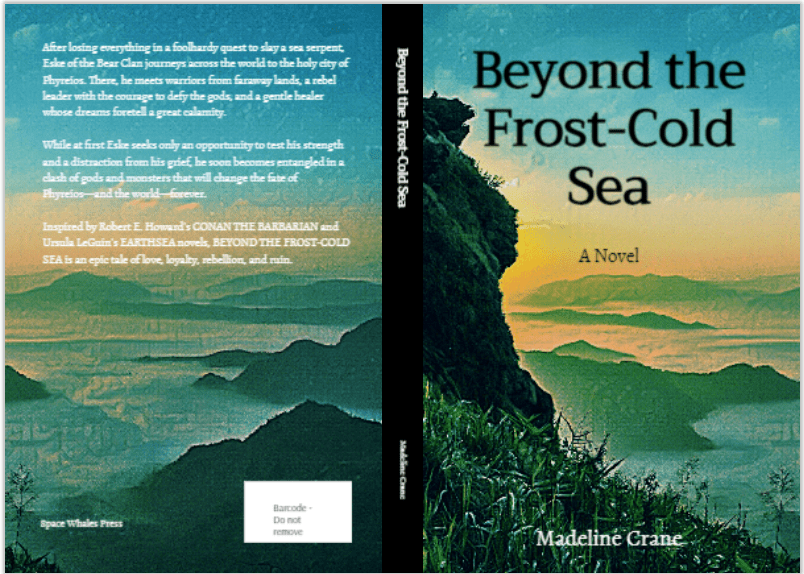

2 thoughts on “Beyond the Frost-Cold Sea Chapter I (Free Preview)”